What Is FluBot SMS Malware? Is It Really Gone? How to Get Rid of It?

On Wednesday, June 1st, Europol announced the takedown of FluBot malware in a coordinated effort from international law enforcement across 11 countries. Although the actors behind the malware campaign are yet to be uncovered, the FluBot infrastructure has been seized by law enforcement.

So, what does this mean for the future of FluBot? Is this infectious SMS worm truly vanquished for good?

What is FluBot Malware?

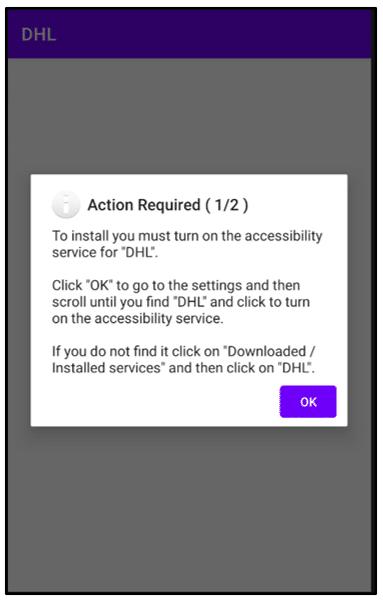

FluBot is a strain of malware that exploits a vulnerability present in Android devices to steal a user’s banking credentials, credit card numbers and passwords, and to distribute messages to more victims. First discovered targeting Spanish Android users in late 2020, the malware abuses the accessibility services feature on Android devices, which enables FluBot to create fake log-in screen overlays to steal sensitive information.

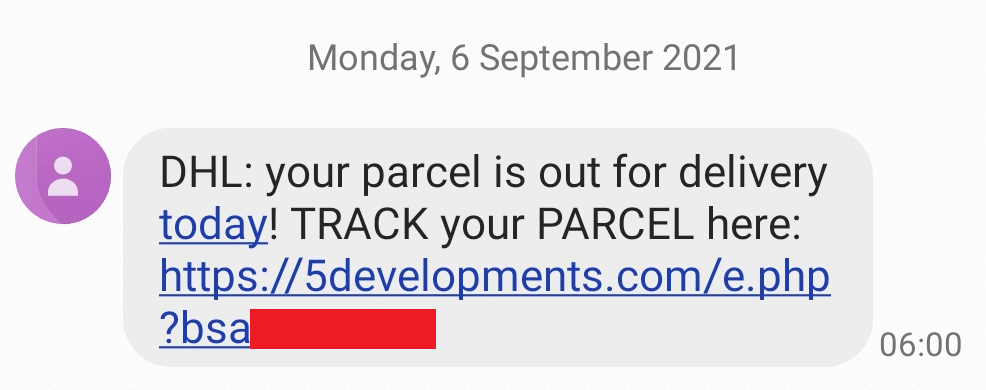

An important capability of this malware is its ability to access the contact list of an infected device, allowing it to self-propagate, spreading rapidly via smishing techniques. Thus, FluBot can be identified as a SMS worm, spreading itself via SMS messages. Since its inception, FluBot has broadened its smishing campaigns to include links to listen to voicemails, download photos, missed deliveries etc. Threat actors even sent messages claiming a victim’s device was infected with FluBot, and that the user needed to install an app (which was, of course, FluBot malware) to rid the device of malicious software. The SMS worm has infected devices across the globe, with some of the majorly affected countries including Spain, Germany and Finland.

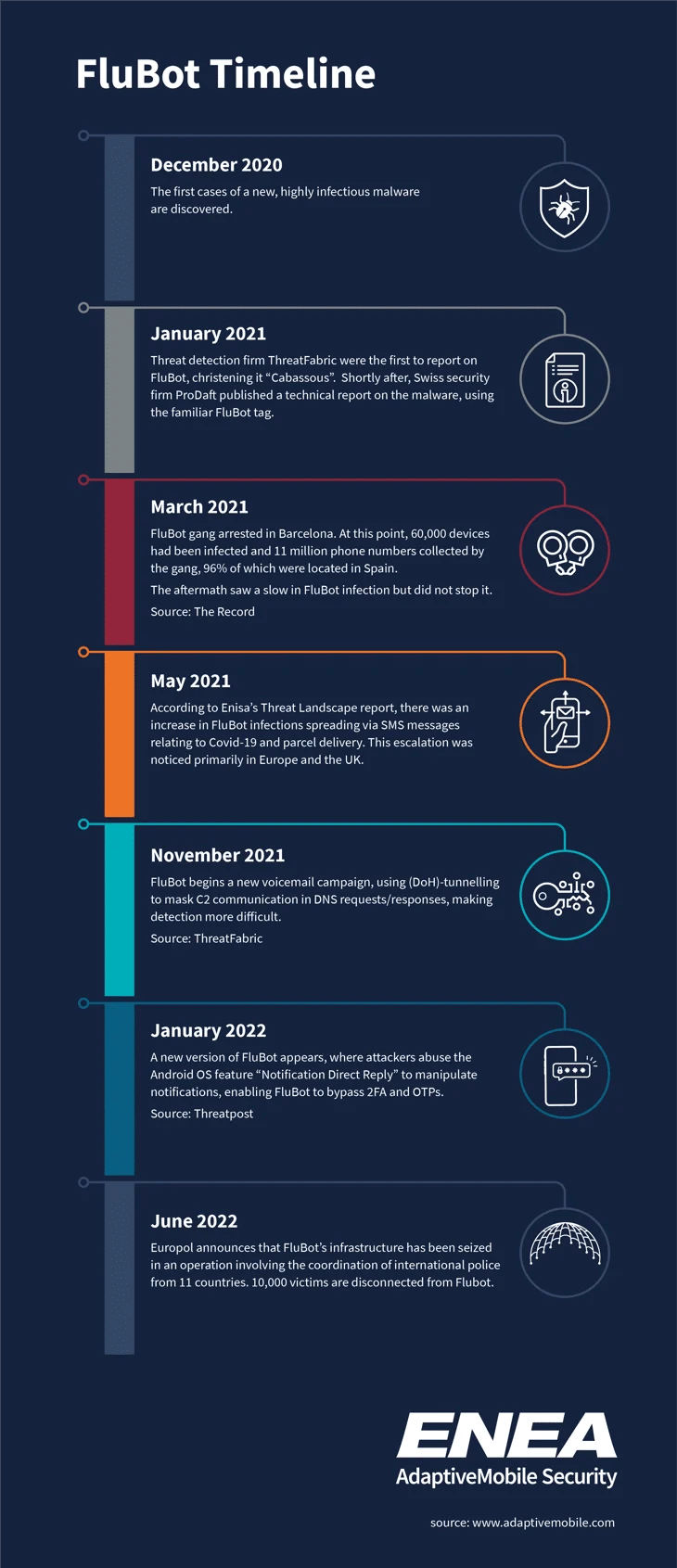

Although Enea AdaptiveMobile Security had previously detected and reported on SMS worms including Selfmite and its evolution, Koler Ransomware and Gazon, relative to other forms of malware, SMS worms were rare prior to the FluBot outbreak in late 2020. The timeline below offers a brief history of FluBot up until Europol’s recent operation.

How does FluBot malware work?

A FluBot attack begins when an Android user receives a SMS containing a malware link. Once clicked, the URL will install FluBot malware onto the device through an APK file. The app, under whatever false pretense it has been installed, will then request additional permissions. This makes FluBot an administrative or system app, meaning it cannot be deleted and obtains several intrusive capabilities, the most distinctive of which is its ability to apply overlay screens (injects) to log in pages, allowing it to obtain a user’s banking details, passwords etc. FluBot is also permitted to access the user’s contact list, which is relayed to the command and control (C2) server so that these users can be targeted with the SMS worm. Messages are sent from an infected device and are deleted from the “sent items” folder, so the user is unaware their device has been compromised. FluBot uses a Domain Generation Algorithm (DGA), allowing it to swiftly shift to another domain in the event of the domain in use getting taken down.

An example of one of the SMS messages sent to Android users:

FluBot requests permissions:

FluBot malware continuously evolved to remain effective, with new versions of the malware being discovered regularly by researchers. One of the most significant milestones in FluBot’s evolution was when it began to use DoH (DNS Over HTTPS) Tunnelling as an indirect way of communicating with its command and control (C2) server. This made it more difficult to identify these messages as suspicious traffic, as DNS requests were encrypted and no longer going directly to FluBot’s C2 server. Though FluBot’s primary target is Android devices, where the exploitable vulnerability lies, these smishing messages have also been sent to IOS users, with the included link redirecting the victim to a malicious website, maximizing the reach of FluBot’s campaign.

The End of FluBot?

So, FluBot infrastructure has been confiscated by the authorities. What are the implications of Europol’s victory moving forward? Is it just a matter of time before the original FluBot resurfaces?

The high success rate and longevity of FluBot’s campaign makes it enticing for other bad actors to attempt to replicate the SMS worm, and we have already observed other malware campaigns, including Medusa and Anatsa, mimicking elements of FluBot and using the same distribution network. As long as these SMS worms are effective at infiltrating devices and result in financial gain for the attackers, they will continue to be created and spread.

It’s important to note that the people behind FluBot, those who created it and designed the malware campaign, have not been identified, and may never be. This begs the question as to whether these attackers will revive FluBot or something similar themselves. Considering the many ways that FluBot evolved since its inception, with the malware writers going to new lengths each time to expand its methods, capture more victims and bypass security measures, it is not unrealistic to assume that these actors will attempt to set up a new command and control server and create new botnets to bring back the SMS worm. Perhaps there are other established attacker networks that could be used to facilitate an accelerated resurgence in FluBot, and if this is the case, will these attackers have another 2-year head start on law enforcement?

How can operators protect their subscribers?

Though it is likely that we have not seen the end of FluBot, Europol’s seizure of FluBot infrastructure has had a positive impact in the short-term, having disconnected 10,000 potential victims from the malware’s network. While this effort from international law enforcement has made some headway in the fight against FluBot, it is unfortunate that mobile operators could not do more to protect their subscribers from the SMS worm due to privacy regulations. Going forward, operators will benefit from practicing a joined-up messaging security focus, rather than fixating on protecting subscribers from SMS alone, as we know that FluBot graduated to MMS and (on a smaller scale) RCS transmission when the malware campaign became more advanced. This is especially important as we continue to migrate over to 5G, which allows for so many forms of messaging. FluBot transmission and infection is still very much possible in 5G networks – read more about securing SMS in 5G here.

We should assume that FluBot malware will return in one form or another, and must be prepared for when it does. Security is a key differentiator for carriers to protect subscribers and their brand’s reputation. Enea AdaptiveMobile Security’s award-winning Managed SMS Firewall helps operators protect their subscribers from SMS threats including smishing attempts. We protect 2.4 billion subscribers from unwanted and dangerous SMS spam and have previously detected and blocked messages attempting to spread SMS worms to Android users. Discover more about our Managed Messaging Firewall and Threat Intelligence services.