The Mobile Network Battlefield in Ukraine – Part 1

Note: This blog was updated on the 4th of April to reflect recent new information from the SSSCIP on call blocking

It has been nearly 5 weeks since Russia’s new invasion of Ukraine. Prior to the invasion on February 24th 2022, a number of observers worried or believed that the Russian offensive would involve co-ordinated large amounts of IT attacks on key infrastructure, including on Ukrainian communication networks. The effects of these attacks would have been globally widespread and publicly felt. However, headlines regarding cyberattacks since the invasion had been muted, although there have been some public reports on the use of cyberattacks on Ukrainian national critical infrastructure.

What has slipped many commentators by, however, has been the unprecedented involvement of mobile telecom networks in this conflict – especially in how they have been defended, maintained, and used. As a follow-up to our previous paper on the use of telecom networks in Hybrid warfare, we discuss here what has occurred since the Invasion. In this multi-part series of blogs we will first discuss what the Ukrainian mobile operator community did since the invasion, and the profound implications of the use of Telecom networks on the battlefield and in the wider conflict. In our 2nd blog, we then document the impact this war on our idea on cyber warfare, and then in our final blog what we can expect in the future in the conflict in the mobile telecom sphere.

The Ukrainian Mobile Operator Landscape

Even before the new invasion in 2022, and since then, the Ukrainian Mobile Operator Community have taken many massive and impactful steps to both defend their mobile networks, and to ensure its resilience. Before we go into detail on this, it is important first, to realise the extent of mobile penetration in Ukraine. Mobile phone ownership rates are at ~130% of the population, which means the vast majority of the population own a mobile phone. There are 3 main Ukrainian Mobile Operators: Kyivstar(26 million subscribers), Lifecell (10 million subscribers) and Vodafone Ukraine (19 million subscribers) along with an additional small mixed MNO/MVNO mobile operator called TriMob or 3Mob (0.3 million subs) which piggybacks on Vodafone Ukraine outside of Kyiv – and is the mobile wing of the fixed line incumbent operator Ukrtelecom.

Timeline

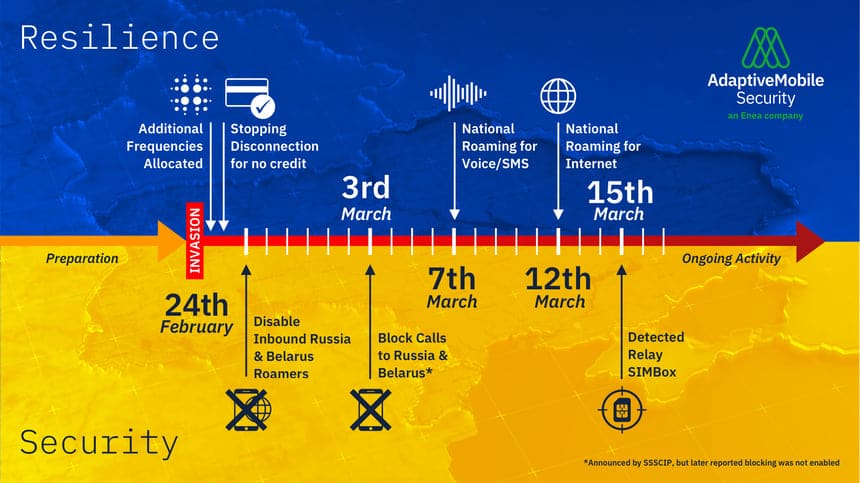

Many significant decisions and actions have been taken since the start of the new Russian invasion, but the timeline below outlines what we believe are the most significant ones:

On the day of the invasion (24th of February) – several key decisions were made. Firstly, the Ukrainian Telecom regulator (NKRZI) announced that they had allocated the three main Ukrainian operators additional 3G and 4G frequency bands. The stated purpose was to provide more capacity to locations where it was expected people would flee (urban areas and the western border areas), but this frequency increase was implemented countrywide, meaning the entire country would benefit from the extra capacity.

Also on that day the Ukrainian mobile operators and Ukrtelecom made the co-ordinated decision not to suspend any account in the event that any subscriber ran out of credit. This decision meant that everyone could stay in contact, even if they were in a position or situation where they could not obtain any additional credit (due to mobilisation to the army, unable to buy credit in a shop, or any other disruption). This decision was prompted by a request from the SSSCIP (State Service of Special Communications and Information Protection of Ukraine), also known as the DSSZZI, who are the technical security and intelligence service of Ukraine.

Finally, and most impactful from a security standpoint, on the night of the 24th/25th of February, all 3 main Ukrainian mobile operators, with the decision of the NKRZI, suspended all inbound roamers from Russia and Belarus. This was a profound security move, and unprecedented in that no country in the world has ever blocked all mobile phone users from neighbouring countries which with it had previous roaming agreements. Immediately, mobile subscribers from Russian and Belarusian mobile networks could not roam onto and use the Ukrainian networks. At a stroke this action wiped out a backup communications system for the Russian invasion forces. Also, at a cybersecurity level, this decision also made the Ukrainian core network attack surface (3G/4G) less vulnerable to known Russian-originated threat actors over the global SS7 and Diameter signaling protocol links.

On the 3rd of March, the Ukrainian mobile community took further security and resilience steps. The SSSCIP announced that Ukrainian mobile operators had made an additional security move to block all phone calls made from Ukraine to Russia and Belarus. As a result even if Ukrainian SIM cards came into possession of, or were being used by the invading Russian forces, then they could not be used to make phone calls to Russia. UPDATE 04/04/2022: Despite the earlier SSSCIP announcement that this call blocking in place, according to an interview on the 2nd of April with Yuriy Shchyhol, Yurii ShchyholChairman of the SSSCIP – call blocking did not occur, instead, call eavesdropping of calls from Russian forces to Russia has been occurring on an on-going basis.

Next, on the 7th of March, National Roaming was announced with all 3 mobile operators participating, in co-ordination with the SSSCIP and the NKRZI. The stated reason for this was to overcome disconnection from communication in the Kherson and part of the Nikolaev areas. However, the initial actual regions (oblasts) covered many eastern and central areas, and the implementation is then to be rolled out nationwide. This meant that mobile subscribers, for any one Ukrainian mobile network could now use the network for any of the other 2, for Voice and SMS.

The logos used by Vodafone Ukraine, Lifecell, and Kyivstar respectively to announce National roaming. Source: Vodafone UA Lifecell, Kyivstar via facebook

National roaming, also termed Emergency Roaming is a concept that has often been discussed for mobile phone networks, but again this was a world’s first in that it never been implemented by any country for any extended period of time. Isolated cases in the past have included T-Mobile and AT&T sharing radio access in an ad-hoc manner after Hurricane Sandy in 2012. By doing this, the authorities have massively increased the ability for the Ukrainian population to use their mobile networks. This meant at a practical level, that even if one or 2 of the mobile operators had damaged or de-powered cell-towers in an area, as long as a single operator served an area any Ukrainian mobile phone subscriber could use it. National roaming was further enhanced on the 12th when limited 2G/3G internet was made available. This meant that people using the service could use popular messenger apps to communicate, as well as voice and SMS.

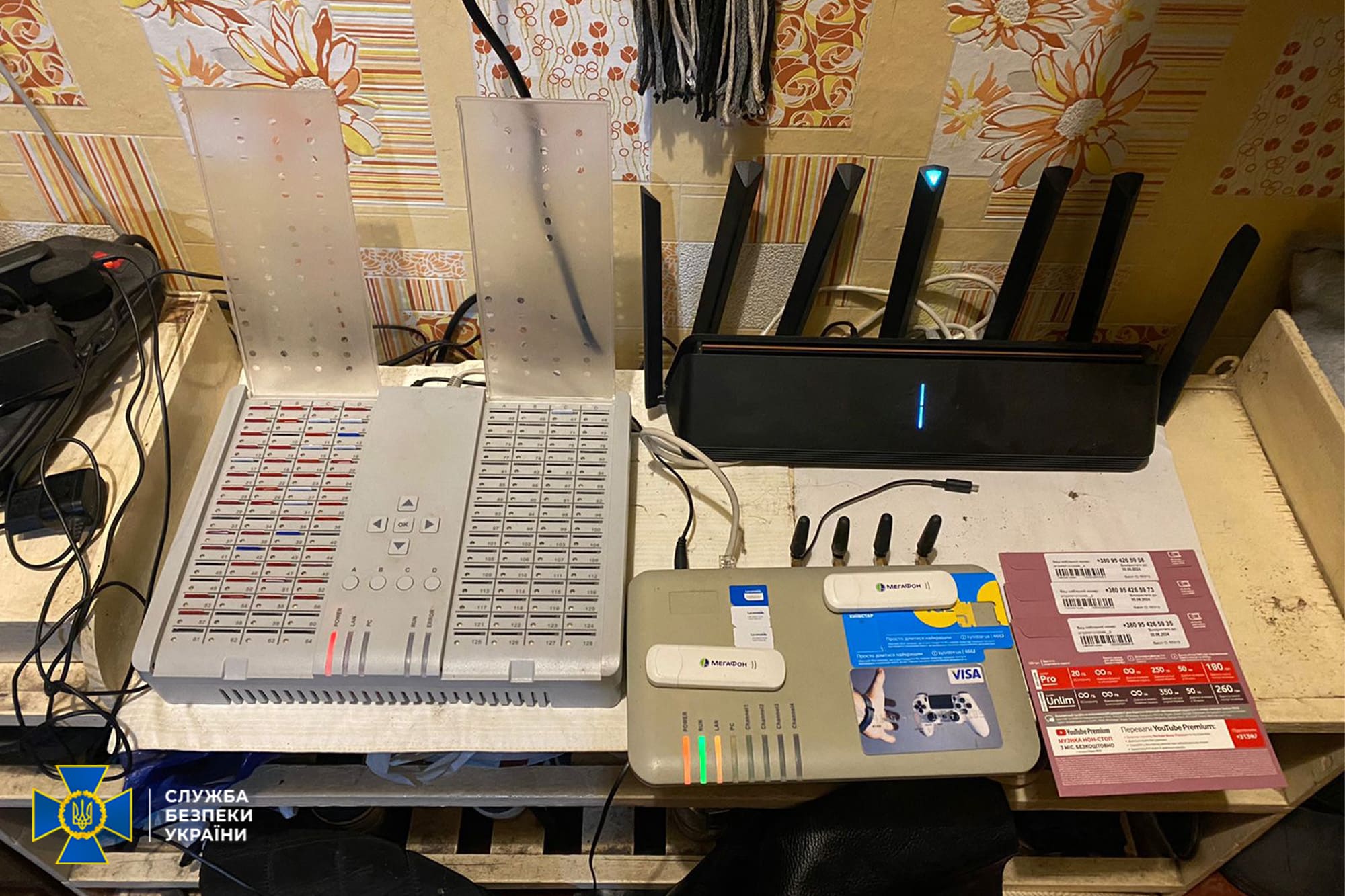

Finally, as a specific, important incident of mobile telecom security affecting the battlefield, on the 15th, the SBU (Security Service of Ukraine) announced the capture of a SIM Box. This was being used as a voice call relay from Russian forces’ leadership in Ukraine, as well as being used to send text messages to local targets. This is an example of the use of Ukraine’s mobile phone network by the Invasion forces, and the ongoing battle to detect and secure it. Specifically the SBU quoted that the SIM Box had:

- made anonymous phone calls from Russia to the mobile phones of the invaders in Ukraine;

- sent SMS to Ukrainian security officers and civil servants with proposals to surrender and side with the occupiers;

- passed commands and instructions to advanced groups of Russian invaders.

Pictures of seized SIMBank+ 3 GSM Gateway(s). Source: SBU via twitter

It was also reported that up to a thousand calls a day were routed through this system, many from the “top leadership” of the Russian army. Its setup of a commercial, off the shelf Hypertone SIMBank, + several multiple Hypertone GSM Gateways and control software was used to relay phone calls made from mobile phones within Ukraine to IP, in order to send back to Russian addresses. This system looks to have been designed to avoid call interception by trying to ‘blend in’ i.e. by dialing in-country only, and then using IP to bypass the blocks on outbound calling to Russia. The use of a fragile system such as this seems to have been a forced development driven by the poor state of Russian military communications and the fact that Ukrainian mobile operators had blocked outbound calls and Russian subscribers, leaving very little room for the Russian forces to ‘move’ in having to setup a communication system like this.

Other Security and Resilience Steps

While these were large co-ordinated or impactful moves by the Ukrainian mobile community, there had been a constant series of other decisions made. These range from the large to small :

- The Ukrainian mobile operators making free or greatly reduced roaming available for their subscribers who go to more and more countries in Europe. This has given those who have fled abroad the chance to communicate and stay in touch with those who are staying in Ukraine – which is a powerful psychological boost to both the defenders and those who have fled the country.

- Ongoing improvements within the National roaming framework. Namely the addition of TriMob into the National roaming agreement with Lifecell on the 13th , and then with Kyivstar on the 17th of March.

- Specific mobile network security decisions and actions, made by the Ukrainian mobile operator community, regulator and security service. Many of these have not been made public, but some that have been include:

- The recommendation from the NKRZI on the 28th of February to block 642 ASs (autonomous systems) of the “RuNet”, i.e. Russian internet, which together cover 48 million IP addresses. This was done to prevent cyberattacks of information disseminated from these sources over both fixed line and mobile networks.

- Kyivstar blocking the receipt of all inbound SMS from Russia/Belarus, to prevent spam or fake information from mobile networks in these countries.

- The reported on-going ‘PsyOps’ targeting , via text messages, of Russian soldiers who have been identified to posses Ukrainian SIMs. Those that have been identified are being sent SMS encouraging them to defect and surrender with details, as in this case which reportedly lead to a Russian Soldier deserting with his tank.

- The constant ongoing search for other malicious telecom equipment. Two examples are on the 22nd of March the SBU announced the detection and seizure of a “network of bot farms located in the largest cities of Ukraine, including: Kyiv, Dnipro, Odesa, Vinnytsia”. These SIM boxes had been sending out SMS messages aimed at fostering enmity within the Hungarian minority in the Transcarpathia area of Ukraine. Another detection by the SBU were the 5 bot farms on the 28th of March, where SIM boxes compromising over 100 SIM Gateways were used to sign up to social networks to “spread misinformation” and cause panic.

It would be remiss not to mention the on-going and heroic efforts of the Ukrainian mobile operator and equipment personnel to keep cell towers and their supporting critical infrastructure, connected and powered up. This has meant that the mobile networks have stayed functional for far longer than would normally be expected, in areas featuring destructive strikes on telecom infrastructure such as underground fibres and cell-towers, as well as power outages.

Repairing of Telecom Fibre. Source: SSSCIP via twitter

There are multiple moves that Mobile Operators, and the state as a whole can take when preparing themselves for any conflict that may involve telecom networks. Our previous paper on the use of telecom networks in Hybrid warfare covers many of these recommendations, however key principles are that these plans and techniques should be co-ordinated and in place prior to any situation in which they might be used. As can be seen when we review the above, Ukraine has been instrumental in co-ordinating and preparing their mobile networks to the position where they are today – a much stronger position than many observers may have expected before the conflict. In our next blog we will discuss the impact of these security and resilience steps of the Ukrainian Mobile networks, and the effects these have had on the progression and course of the war itself.