SMS Phishing / Baiting Attack: What Happens If You Take the Bait?

Welcome to the first in a new 3-part blog series on messaging security. In this blog, I will be introducing deceptive SMS phishing attacks, explaining how they work, and how threat actors can profit off them.

Most of us have been exposed to phishing attacks or are at least aware of this threat, but I’m going to start off with a quick definition for those who might not be clear on exactly what phishing attacks entail. Deceptive phishing can be defined as a social engineering technique whereby an attacker tricks the victim into sharing sensitive information by pretending to be a trustworthy entity. Phishing scams have become particularly prevalent over SMS (smishing), which is the type of attack that I will be focusing on in this blog. There are four main stages of these messaging attacks, described below using the example of a phishing attack where the threat actor masquerades as a financial institution.

Initiation of a Deceptive Phishing Attack

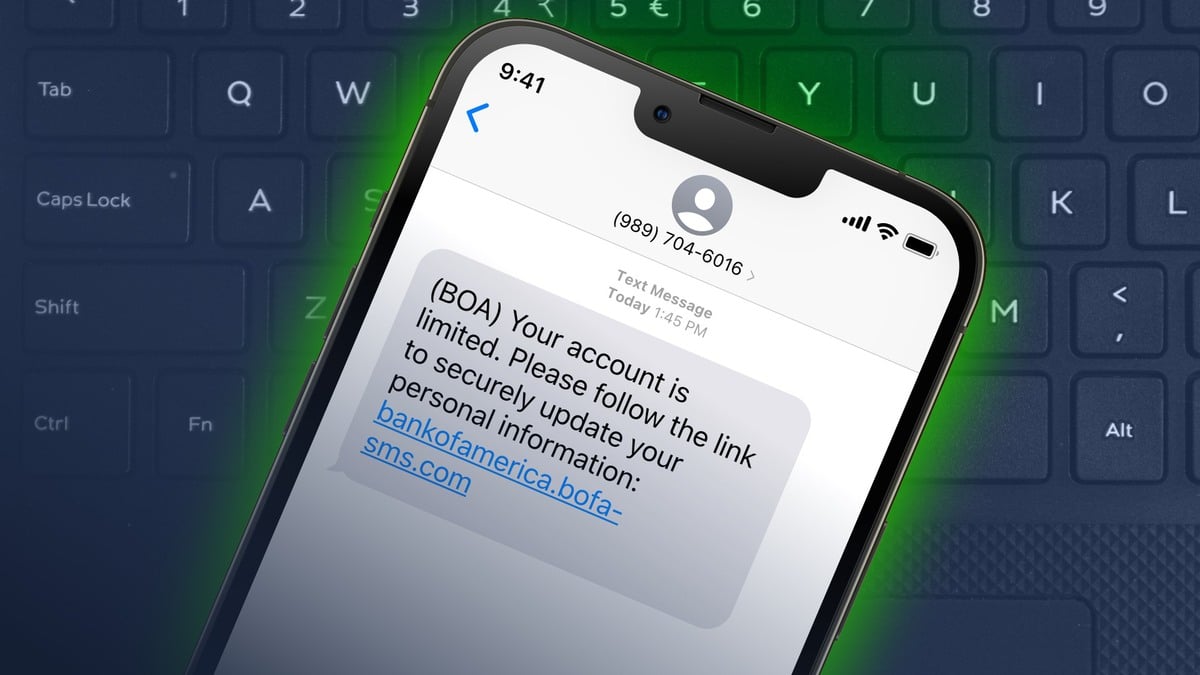

The phishing attack begins when the mobile user receives an initial message on their device which, in this example, appears to be coming from a financial institution. There are two distinct types of attack, which can be differentiated by the way in which the attacker targets the victim. In this blog, I will be using North America as a case study, though these attacks are affecting mobile subscribers globally.

The first type of attack is used to target mobile users who are customers at regional institutions. To boost the credibility of the message, the attacker uses a virtual phone number to make the message appear as though it has been sent from a local number. This is a commonly used attack behavior in areas where banking is more localized – in North America, many of the banking institutions used by residents are located within the region. Virtual phone numbers are commonly used by scammers as they are extremely difficult to trace and offer anonymity.

The second method is to disguise the attack as a message from a national financial institution. This is often done by spoofing the short code used by a financial institution to send messages to customers. This means that the attacker can send a message which appears to be an addition to the thread of genuine messages the customer has previously received from his/her bank. This tactic has been observed in an SMS bank phishing campaign in Ireland, as well as in other contexts such as Covid-19 related messages purporting to be from public health bodies. By making it seem as though the message is coming from a credible source, the attacker aims to gain the trust of the victim and trick them into handing over sensitive information.

Once the message has been received and the victim engages with it, the attack commences.

1. A Call-To-Action: The Phishing Link

The attack messages will contain a call-to-action (CTA). There are two primary types of CTA, both with the intended use of extracting information from the user. The first type is a prompt within the message to make a phone call (voice phishing). For example, the message may claim that the user’s card has been deactivated, and they must call a specified number. If the victim responds to this, they will be asked to give their credit card details over the phone – often via an Interactive Voice Response (IVR) phone call. Alternatively, the user is redirected to a website via a phishing link, where they will be asked to input their credentials. The attacker often creates a sense of urgency to apply pressure to the victim in an effort to override rational thinking. Unfortunately, this can be a highly successful social engineering tactic.

2. Extraction

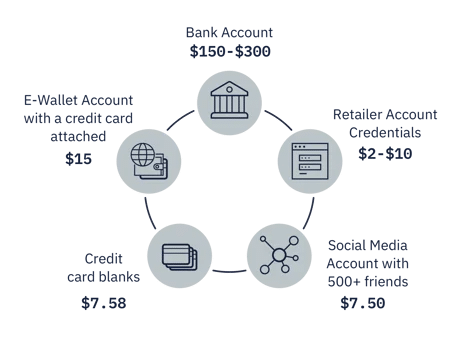

The third stage of the attack occurs once the attacker has successfully extracted the desired credentials from the mobile user. This is valuable information which the attacker then seeks to sell on the dark web. The value varies depending on the type of information the attacker possesses. Below are some examples – specific to North America – of different credentials and what they can be worth on the black market, starting out at $7.50 for a social media account with five hundred or more followers and rising to $300 for an individual’s bank account details.

3. Exploitation

Once a buyer has purchased credentials from the dark web, they can use it to launch their own attack. In the case of a bank account, for example, the victim’s information is used to log in to their account, where the attacker can change the password, giving themselves primary control. At this stage of an attack, the threat actor may implement additional capabilities, such as redirection, where the attacker has communications to a victim’s account redirected to themselves. An attacker may also intercept the victim’s communications. A common method of interception is to use Sim Swap – a service which allows users to switch between SIM cards without changing their phone numbers. Attackers have been known to weaponize this service, using personal information to have the victim’s phone number ported to the attacker’s SIM. This allows the attacker to commandeer the user’s phone number, enabling them to intercept communications such as two-factor authentication, required to access the victim’s bank account details. Needless to say, these attacks can result in significant monetary loss for the victim.

Conclusion

It is important to note that, although financial services firms are a popular target for deceptive phishing attacks, A2P messaging attacks do not only come in the form of banking communications. Sending messages purporting to be from established organizations, such as Apple or Microsoft, is another way these threat actors disguise their attacks. Many of these attacks will use shortened URLs in their messages, which help to disguise the domain of the malicious website that the user is being redirected to. Job SMS scams, for example, use shortened URLs in messages disguised as job opportunities and have been observed to be particularly prevalent in the New Year.

These phishing scams are not going anywhere. Due to the continued use of SMS over 5G, SMS spam will remain a threat to users. In fact, we may see an increase in threats due to 5G network slicing allowing more entities to utilise slices, which would have access to large scale SMS sending infrastructure. Mobile users should continue to be vigilant (learn how to spot and react to these scams here), as should MNOs – ensuring the protection of subscribers needs to remain a priority.