Understanding and Detecting IMSI Catchers around the World

One of the good things about working in the area of core network security, is the opportunity to find new and unexpected types of attacks. These are attacks you didn’t even know could happen, much less have a chance to prevent. Finding these unexpected attacks doesn’t just happen though, it requires experience and investigation, but most importantly it needs the mindset to dig deeper into any strange events that are encountered, and try to understand them, rather than just assuming they are random malicious events.

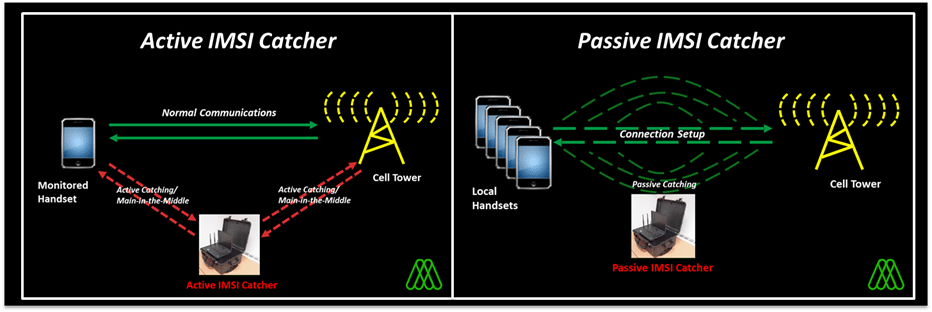

In this particular case, we are discussing IMSI Catchers. First off, the term IMSI catcher is a misused and sometimes contradictory term however. As explained here, there are actually 2 types of equipment that those in the public (and many in the industry) would conflate into what they would call IMSI catchers.

- ‘Active’ IMSI Catchers, also termed Cell Site Simulators (CSS) or Fake Base Stations – these attempt to force local devices to connect to a Call Site Simulator, in order to decrypt the conversation and texts, and to execute man in the middle interception. These would be considered the more ‘traditional’ type of IMSI catchers most would be aware of. Stingrays are also a common term used for these (named after the brand built by Harris Corporation). A good overview of how the Active IMSI /Cell Site Simulators work is here.

- Passive IMSI Catchers – these passively listen into the paging of mobile devices as they move and register to new real Cell towers in the local area, in order to get the IMSI numbers of these devices. They are far less precise, and are unable to do any of the more sophisticated type of interception, but involve no interaction between the mobile device and the IMSI Catcher. An overview of how these could work, and how they function is here.

The primary difference between these two is that the more traditional Active IMSI Catcher/CSSs always involves some form of interaction with the mobile device, whereas the Passive IMSI Catcher doesn’t – it literally just listens in to the paging that occurs in the local areas as the mobile device changes between legitimate cell towers in the vicinity. This makes a big difference when it comes to detection of these IMSI Catcher types.

A lot of research has gone into various ways of detecting Active IMSI Catchers, by looking at how they differ from real Cell towers. One distinctive example of what an Active IMSI Catcher might do is the forced downgrading of their target mobile device to use a less secure radio interface. This detection of an Active IMSI Catchers can be difficult, involves a lot of local measurements and often can and has in the past led to false positives, but it gives some results. From the attacker’s perspective it’s also a trade-off in that they must make the effort to physically deploy an Active IMSI Catchers in a sensitive area, and then hope its radio activity doesn’t give it away. This is often why more sophisticated attackers may often resort to using attacks over signalling interfaces such as SS7 and Diameter to achieve their aims, which can be sent from any part of the world.

A Passive IMSI Catcher changes things somewhat. It still involves physical deployment of a system to listen in the local targeted area, but it is essentially undetectable on the radio interface, as it emits nothing that would allow it to be detected. This makes it very valuable to perform long-term surveillance in sensitive areas, when the goal is to have the least chance of being detected, while still trying to determine the IMSIs of who is in the local area.

The issue with both types of IMSI Catchers, from the attacker’s perspective, is that what they are left with are a collection of IMSIs from around the world. While this information may be useful, often you need more information to profile who has been ‘caught’. For Active IMSI Catcher deployments; the attackers may also intercept calls/text messages etc, so have a better idea of the target, but for passive IMSI catchers they won’t have that. What the attackers really need is the co-corresponding phone number – the MSISDN of the mobile device associated with the IMSI – in order to truly figure out the identities of the mobile device their IMSI catcher has caught.

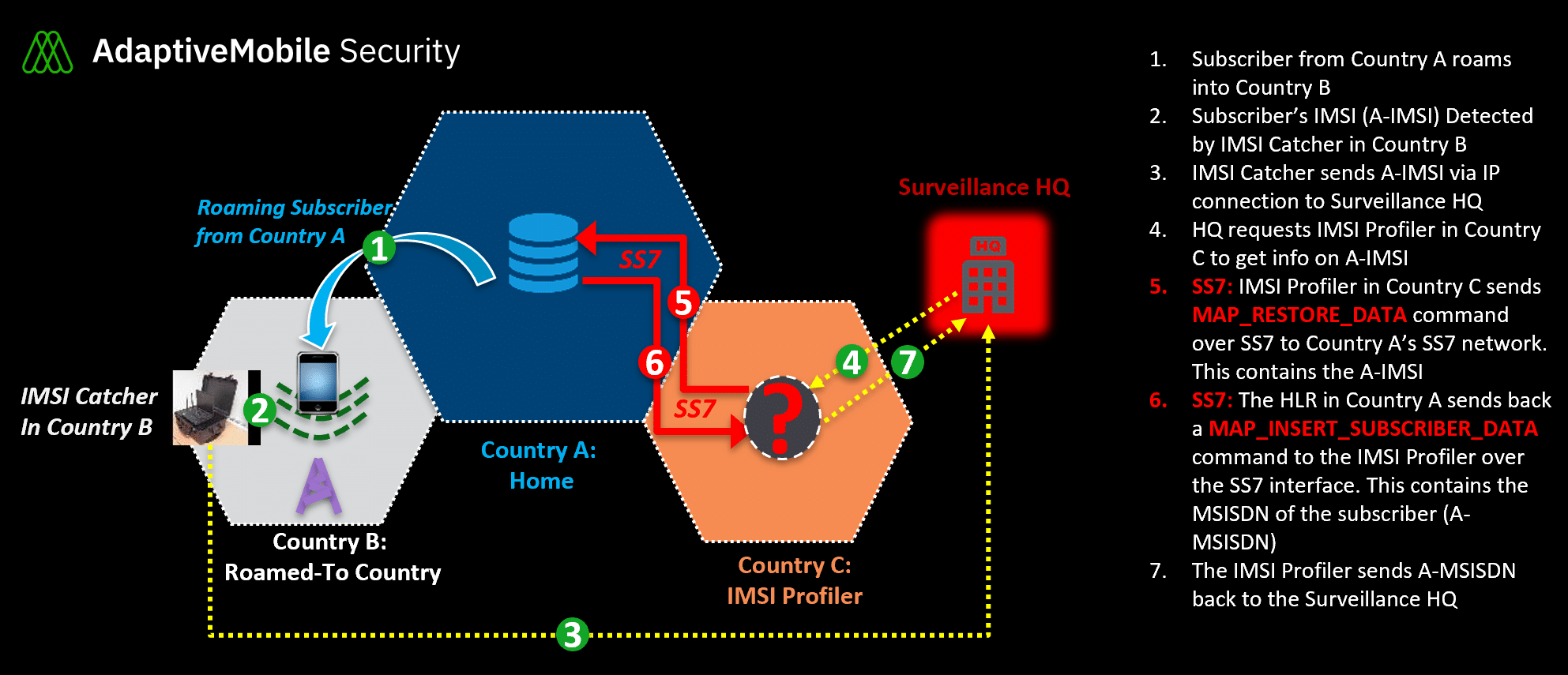

This is where our analysis and investigation has come in. Over time, we have been seeing patterns of unusual requests over the SS7 interface, for particular IMSIs. Specifically, what we have been seeing is our Signalling Firewalls, deployed at multiple customer mobile operators, receiving suspicious MAP_RESTORE_DATA packets for IMSIs from unexpected sources. A MAP_RESTORE_DATA packet is a particular command that requests that the home operator sends details for a particular IMSI to the roamed-to network. Details in this case includes MSISDN (the actual phone number), call forwarding setting and other specific information. Further investigation showed that we always received this command when these IMSIs were near or attached to specific Cell Sites while roaming in a 3rd country and nowhere else.

Our working theory, is that what we are observing is what we now call “IMSI Profilers”. These IMSI Profilers work in conjunction with IMSI Catchers – they take the list of IMSIs that have been detected and request profile information, in order to feed these phone numbers back to the IMSI catcher operator. The sequence of events that we believe to happen is shown above. From log analysis it also seems likely (but can’t be confirmed 100%) that the IMSI Catcher in the 3rd country is of the passive variety. In this particular case, the IMSI Profiler is using a source SS7 address (called a SCCP Global Title or GT) in a small European mobile operator that we have detected previously in our SIGIL/Signalling Intelligence system to be used by multiple surveillance companies, further confirming our suspicion that it is malicious.

Regardless of the IMSI catcher type used, this method of analysing incoming suspicious signalling activity gives the opportunity for mobile operators to partially protect their subscribers against IMSI Catchers around the world, something they didn’t have in the past. It won’t stop an Active IMSI Catcher from forcing a subscriber to connect to them, but it would stop additional information being retrieved. And in the case of passive IMSI catcher it is potentially one of the only ways to detect these remotely and block any more useful information being obtained.

In the long term, improvements in the new 5G radio and core network standards means that mobile operators should be able to greatly improve the ability to block IMSI Catchers over 5G. If these are implemented correctly and no loopholes are introduced then effective 5G IMSI Catchers may never arise. In the interim however, IMSI Catchers – both Passive and Active – are being used globally in the world to track and record individuals without their consent. By analysing incoming signalling traffic, and detecting and blocking these IMSI Profilers, mobile operators now have the opportunity to help protect their subscribers globally, regardless of how stealthy the IMSI Catcher is.